An scéal brónach faoi múinteoir scoile Árainn agus a bhainisteoir, an Sagart Paróiste.

The sorry tale of an Aran teacher and his boss, the Parish Priest.

|

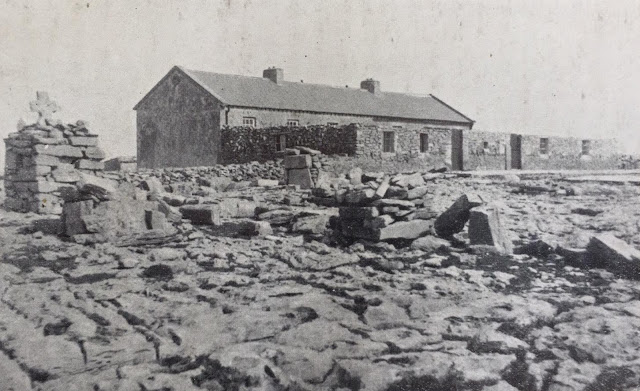

| David O’Callaghan’s old schoolhouse at Fearann an Choirce. He taught here between 1885 and 1911. |

Many of our readers will be familiar with Liam O’Flaherty’s 1932 novel ‘Skerrett’ which was inspired by a famous row between the Fearann an Choirce (Oatquarter) schoolmaster David O’Callaghan (Dáithí Ó Ceallaháin 1853-1937) and his Parish Priest, Murtagh Farragher (Muircheartach Ó Fearhair 1857-1928).

|

| Published in 1932. |

A native of Co Limerick, O’Callaghan had spent five years teaching on Inis Meáin before coming to Fearann an Choirce school in 1885. He had arrived on Inis Meáin with almost no Irish. This would change shortly and he became a committed member of Conradh na Gaeilge when it started in 1893.

Previous to this O’Callaghan was a supporter of the Gaelic Union, which was founded in 1880 by Fr Ulick J Burke. Ulick was an uncle of the radical Peter McPhilpin, who died aged forty five in 1894, as he battled evictions while parish priest of the Aran Islands. (A story for another day.)

While O’Flaherty’s book is loosely based on the events between 1905 and 1914, it is at the end of the day a work of fiction. Having read ‘Skerrett’, researching the facts of the dispute can be confusing as one tries not to mix up what really happened with what O’Flaherty wrote.

For obvious reasons, changes were introduced in the novel. Some for artistic and some probably for legal reasons. The danger of drawing inaccurate conclusions based on the book is something we hope to avoid.

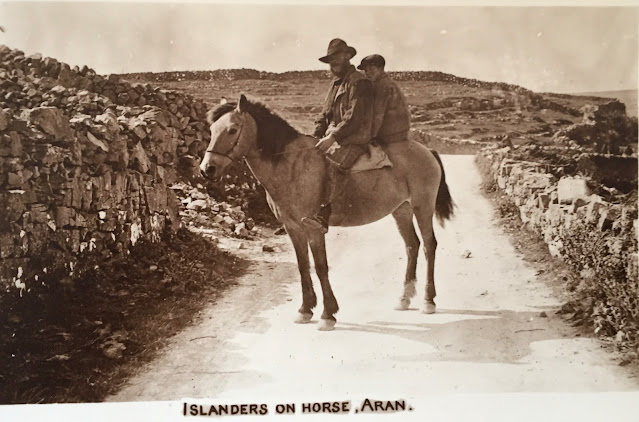

The animosity between Fr Farragher and David O’Callaghan is said to have started when David didn’t send a horse for the priest on the occasion in 1905 of the ‘Station’ being held in the teachers house.

|

| Aran horses from around 1900 to the present day |

Like the origin of most rows, it’s likely that this was just one of a few reasons why the two men clashed. A case perhaps of the straw that broke the horse’s back.

Murtagh and David were men of strong views and stubborn mentality.

|

| Photo kindly supplied by Murtagh’s Gr Grand nephew and namesake. |

|

| David O’Callaghan |

Fr Farragher had first arrived on the island as curate in the late 1880s under Michael O’Donohoe and returned as Parish Priest from 1897 to 1920. We came across Murtagh before in a piece we did on a harrowing visit Michael Davitt and an American journalist paid to the island during distressing times in 1888.

His return in 1897 would see Murtagh involved in many schemes and initiatives which benefited the islands greatly. However, his authoritarian ways would not go unchallenged, leading to an incident which got world wide coverage in 1908.

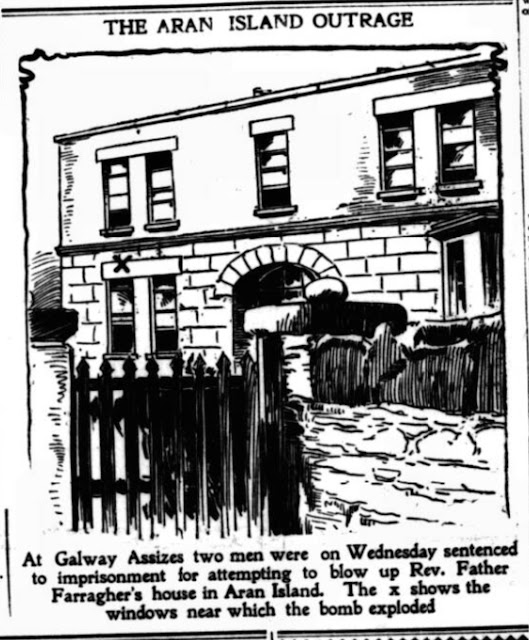

This involved the local islands publican and bailiff, Roger Dirrane, being convicted for Bombing his house in 1908. We wrote about this some time ago and the aftermath of that incident would have a bearing on the row between the priest and the teacher.

|

| A sketch of the priest’s house from 1908. Shortly after the explosion. |

It is important to try and understand the relationship in Ireland between National School teachers and their employer, the local Catholic or Protestant clergyman. The National school system had been established in Ireland in the 1830s.

In order to combat religious intolerance, it was intended to be strictly non-denominational but before long the two denominations, realising the vital role segregated education plays in religious formation, had succeeded in gaining control. This meant that while the salaries were paid by the state, the priest or minister had control of hiring and firing.

Segregated education was also a defence from what all churches regarded as a great misfortune - mixed marriages.

From the establishing of National Schools in 1831 until 1878, the teaching of Irish, or through Irish, was prohibited. O’Callaghan embraced the new freedoms despite occasional parental encouragement to prioritise their children’s ability to speak English.

|

| The result of pressure for change. |

Murtagh had a history of getting things done and this inevitably led to confrontations with those who refused, in even the slightest way, to bow to his authority. The list of the many benefits he brought to the islands is long but so too is a list of all the people he clashed with.

The year after returning as Parish Priest, he was involved with David O’Callaghan in the setting up of a branch of Conradh na Gaeilge (Gaelic League) in Cill Rónáin in 1898. Among those attending were the language activist Tomás Bán Ó Conceanainn (1870-1961) from Inis Meáin and the eighteen year old Pádraic Mac Piarias (1879-1916).

While Fr Farragher was elected as chairman, recognition was given to the prominence of O’Callaghan in furthering the Irish language cause, when he was invited to address the meeting.

|

| Established at Cill Rónáin in August 1898 |

|

| On the deck of this great ship in July 1895, David O’Callaghan made a very telling point about the importance of the Irish language |

|

| The old schoolhouse in Cill Rónáin on the extreme left. Now the location of Halla Rónáin but the venue for the Gaelic League meeting in 1898 |

Fr Farragher was elected chairman as he had a history of support for the language and was a fluent speaker of his native Mayo dialect.

His high regard for the Gaelic League would not last long and in 1901 a very bitter and public feud between the two would break out over sermons in English. The radical weekly newspaper ‘An Chlaidheamh Soluis’ (Sword of Light) featured a number of accusations and rebuttals between 1901 and 1902.

One of the editors at the time was Antrim native Eoin MacNéill (1867-1945), who was a regular visitor to the islands. (One of the stars of the 1934 film, ‘Man of Aran’, 15 year old Maggie Dirrane, worked in MacNéill’s house in Dublin from 1914 to 1916.)

MacNéill was a personal friend of Fr Farragher but he contributed letters on the controversy after An Spidéal native Eoghan Ó Neachtain (1867-1957) took over as editor on October 8th, 1901. While there had been mention of the English sermons during the summer of 1901, it was only after Ó Neachtain’s appointment that things got very heated.

|

| Teach tábhairne Seán Ó Neachtain i nGaillimh. |

Some of our readers may have enjoyed a drink, a meal or a music session in the pub once owned by Eoghan’s brother Seán (Seaghan) at the famous ‘Tigh Neachtain’ at the corner of Quay Street and Cross Street in Galway.

|

| The writer Eoghan Tom Eoghan Ó Neachtain from an Phairc, sa Spidéal. He was editor of An Claidheamh Soluis during most of the row (Photo with thanks to Seán Ó Neachtain). |

An interesting aside is that two years later in 1904, when Roger Casement visited Oatquarter school, O’Callaghan called on Tom O’Flaherty to show off his reading skills by reading aloud Eoghan Ó Neachtain’s column in the Cork Examiner. For this, Tom was rewarded with a half crown.

As the debate heated up in 1902, Ó Neachtain refused to be cowed and he and Murty Farragher took no prisoners. At one stage the derogatory terms ‘Trinity College Priest’ and ‘Shoneen Priest’ were used and this brought a predictable and furious reaction from Murty.

Fr Farragher tried desperately to frame the debate as an attack on his own commitment to the language. A common deflecting tactic for those under pressure from an uncomfortable truth.

The editor fully acknowledged Fr Farragher’s history of language support but refused to be deflected and kept the focus on the central fact that sermons were being preached in English.

|

| Eoin MacNéill on a visit to the islands U.C.D digital library. |

Eoin MacNéill would later play a prominent role in the founding of the Irish Volunteers in 1913 and was involved in the 1916 rising.

The cause of all the bitterness were reports and comments in the newspaper about the ridiculous situation on the islands where the recently appointed curate, Roscommon native Charles White (1871-1935), had very little Irish.

|

| Thatched cottage where the curate lived. Photo N.L.I. |

Although Charles had registered himself and his housekeeper Catherine Cafferky, as having English and Irish at the 1901 census, it seems he was not confident enough to either preach or administer the sacraments in Irish.

Any interference in clerical matters was not going to be tolerated by Murtagh and he launched a spirited and aggressive defence of his young curate.

The truth of the accusation by the Gaelic League members was beyond question, but this central fact got little prominence as Fr Farragher continued to interpret it as an attack on himself.

|

| Fr White died in 1935 aged 64 |

Preaching in English on the Aran Islands in 1901 meant that many had no idea what Fr White was saying. Even worse was the administering in English of the sacraments, especially confession and matrimony. (Well, perhaps not confession.)

Having a priest with no Irish in an Irish speaking district could lead to disastrous results in the next world. Having a medical officer with no Irish could lead to the same thing in this world.

Humour and ridicule were very effectively used to highlight the serious medical implications. While still a medical student, Séamus Ó Beirn (1881-1935) from Tawin at the eastern shores of Galway Bay, staged a hugely popular bilingual comedy called ‘An Dochtúir’ (1904) which drew great reviews and attention. While it made people laugh, it also highlighted the dangers of a young doctor with no Irish trying to practise in Connemara.

In truth, Murtagh Farragher’s commitment and support for the language was exemplary and he had encouraged the use of Irish in his islands schools. The main target of the comments was of course Archbishop John McEvilly, who appointed Charles White in September 1900 but Murtagh construed it as an attack on both him and on religious authority.

(It has been said the MacEvilly’s predecessor John McHale, had refused to ordain any priest who didn’t speak Irish.)

We suspect that the fallout from this controversy was the start of the feelings of ill-will between the two men, rather than the horse that never showed up. What started out as resentment, went on a journey to mutual dislike and ultimately, hatred.

It would appear that Murtagh made two major blunders during this time.

Murtagh’s first blunder involved his resentment at how Inis Meáin seemed to be attracting so many clerics, writers and academics. In 1900 a Feis had been held there but while many travelled from Inis Oirr, it seems less than expected attended from the big island. It was suspected that Fr Farragher had a hand in this.

Because of his row with the Gaelic League in late 1901, the prospect of holding a summer feis on Inis Meáin in 1902 seemed unlikely to get Murtagh’s approval.

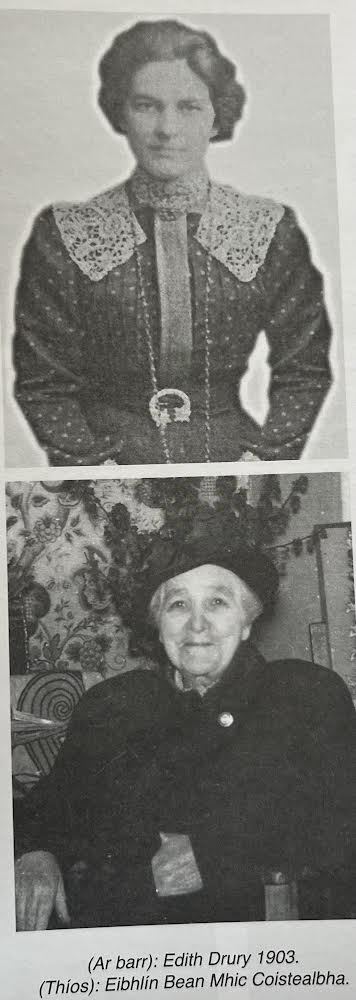

In early August two Gaelic League visitors to Inis Meáin, Agnes O’Farrelly (Una Ní Fhearcheallaigh 1874-1951) and Edith Drury (1870-1962) had suggested a festival under Gaelic League auspices.

|

| Republished in 2010 with an English translation by Ríona Nic Congáil. |

|

| Gaelic revivalist, nationalist and women’s rights activist, Agnes O’Farrelly photo of islanders at Inis Meáin in 1902. Photo U.C.D. Digital library |

They consulted with Fr Farragher when he was over to say mass and they would claim later, that he agreed to them holding an Aeriocht (outdoor celebration) but wanted it confined to the island rather than be a league event. This they agreed to and did not advertise widely. Fr Farragher later denied this.

|

| Edith Drury would later marry Dr Thomas Costello of Tuam. She was a founding member of Coláiste Chonnacht sa Spidéal. (Photo with thanks to Seán Ó Neachtáin) |

The vice President of the Gaelic league, Waterford native Fr Michael O’Hickey, happened by chance to arrive on Inis Meáin around this time. He was unable to get to Cill Rónáin and ask formal permission to say mass in Fr Farragher’s parish, as the steamer that day stopped first at the smaller islands.

He wrote to Fr Farragher but got no reply. Rumour had it that he had been denied permission. It can be assumed that Farragher thought his presence on the island was connected with the Aeriocht and this annoyed him.

He may also have resented many of the islanders on Inis Meáin referring to Fr O’Hickey, who was a regular visitor, as ‘ár Sagart’ (our priest).

|

| An tAthair Micheál Ó Hiceadha (1861-1916) |

Even thought O’Hickey had no part in the writing or publishing of the letters criticising Fr White, it seems his position as vice president of the Gaelic League was enough to convict him of wrongdoing, in Fr Farragher’s eyes.

Fr O’Hickey had, during previous visits, covered for the priest by saying mass on Inis Meáin but on this occasion he had to attend mass like everybody else during the time he was there.

On the day of the Aeriocht, he and the other Gaelic League members had to listen at mass to a sermon in English by Fr White. This seems like a deliberate attempt by Fr Farragher to provoke them further after their earlier protestations as he could have said the mass himself. Although Murtagh had been invited to the Aeriocht, he remained in Cill Rónáin and sent his young 30 year old curate over by currach.

|

| From Cavan woman Agnes O’Farrelly’s book Smaointe ar Árainn. 1902 |

|

| Inis Meáin photos from Agnes O’Farrelly’s 1902 book Smaointe ar Árainn |

Murty’s second blunder involved his furious and petty reaction to the Inis Meáin Aeriocht and the attendance of Fr O’Hickey.

Because of his antipathy to the Gaelic League, he banned his teachers from attending their Feis in Galway in late August 1902. The fact that he had the hiring and firing of these men and women meant that his orders were reluctantly obeyed.

This action would later be described by the controversial Gaelic League priest, Jeremiah (Gerald) O’Donovan (1871-1942) as ‘petty tyranny’.

The Loughrea curate O’Donovan, clashed with his superiors about the lack of church support for the Irish language. He was also the driving force behind utilising Irish rather than Italian artists in the building of the new cathedral in Loughrea.

It’s possible also that Fr Farragher was annoyed when apparently, none of his teachers wrote to the papers to support Fr White. It’s also likely that the editor of ‘An Claidheamh Soluis’ being closely associated with the Galway Feis, played a part.

O’Callaghan was a great supporter of the Feis and his two children, Michael and Mary Anne, had participated successfully over the years.

|

| Photo from University of Galway. |

It must have been humiliating for the two teachers who went to Galway, to have to wait outside St Patrick’s Temperance Hall in Lombard Street and the Town Hall, while the events were being held.

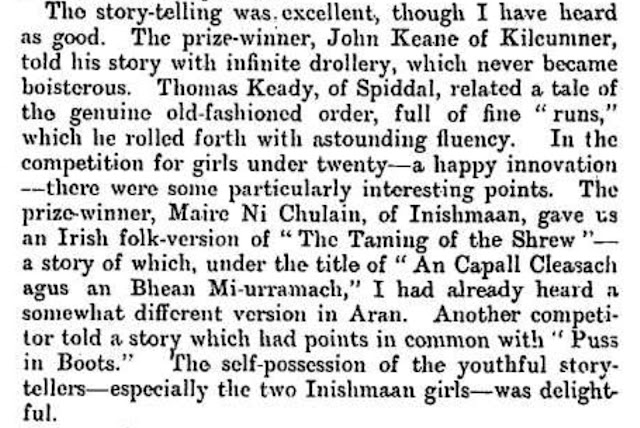

It seems that some competitors from the two smaller islands attended and in a review by Pádraig Mac Piarias afterwards, special mention is made of the prize winners from Inis Meáin and Inis Oirr.

(Pearse also loved hearing the railway porters in Galway cursing in Irish rather than English.)

|

| High praise from the poet Pádraig Mac Piarias |

The Feis was very important to the islanders and on their return in 1904, the girls choir would go on to take the top prize. The sixteen year old Michael O’Callaghan had taken 2nd prize for his recitation in 1903.

Fr Farragher’s ban on his teachers attendance reminds us of the ridiculous situation at the funeral in 1949 of the former President of Ireland, Dubhglas de Híde (An Craoibhín Aoibhinn), one of the founders along with Eoin MacNeill of the Gaelic League.

Only one Catholic member of the cabinet dared to enter the Protestant St Patrick’s Cathedral and the Taoiseach John Costello, his coalition partner, Seán McBride and the rest of his cabinet, instead joined De Valera and his opposition front bench, outside on the street.

In the course of the many words back and forth in the newspapers, both Agnes O’Farrelly and Eoin MacNeill cast doubt on the accuracy of Fr Farragher’s memory and to an extent, his honesty. This became known as ‘The Aran Controversy’

|

| Two women who stood up to Murty, in 1902 |

|

| Fr Farragher’s reaction to the O’Farrelly letter. |

Fr Farragher seems to have taken particular exception to being challenged by Agnes and Edith.

Not to be intimidated, the two women replied to Fr Farragher and came as near to calling him a liar as makes no difference.

|

| Peace broke out shortly after. |

It was suggested in October 1902 by the Chairman of Galway County Council, Joseph A Glynn, that the matter be referred to arbitration. Joseph was a highly respected figure with both the church and the Gaelic League and later his suggestion that Douglas Hyde be involved was added to by Fr Farragher, with the suggestion that the Bishop of Galway join him.

In September 1902, Fr White had been transferred to Knock. By 1903, Fr Farragher had made peace with the Gaelic League and had resumed his membership. This coincided with a major fundraising drive to build a new church and parochial house in Cill Rónáin. The Gaelic League in Dublin became very supportive in this regard.

The death of Archbishop MacEvilly in November 1902 and his succession by John Healy in February 1903, may have heralded a desire to put the whole controversy to bed.

While clashing with the Catholic Church might be regarded as inadvisable in those times, the row did emphasise how the Gaelic League was non denominational as the Catholic Mac Néill and Protestant Hyde had intended and focused without fear or favour, on language rights and heritage.

Before we get back to the row between Murty Farragher and David O’Callaghan, a few words about the man at the centre of the English sermons row.

It’s hard not to feel some sympathy for Fr White who had no say in where he would serve as curate. He reacted instinctively, defensively and foolishly when confronted about his sermons in English, by doubling down and claiming that everybody understood them. This was patently untrue and was the main cause of the escalation of the controversy.

This fib was undermined by the fact that Fr Farragher later wrote of how his young curate had been attending Irish lessons with the schoolmaster James McCarthy in Kilronan schoolhouse. Something his young classmates found highly amusing.

He later conceded that his claim that everybody in church understood his sermons in English was to annoy the Gaelic Leaguers who challenged him. He possibly felt they were well educated, intellectual, outsiders, who were judging him. Priests then were not used to being judged, especially by members of their own denomination.

In one of his letters to the papers, Fr Farragher had mocked some of the Gaelic League women who had bemoaned the wearing of modern clothes by the young women of Cill Rónáin.

This, he added, while they themselves were decked out in imitation Panama hats and wore the latest fashions to Gaelic League meetings. Murty had a point.

After leaving Aran, Charles White went on to have a very distinguished career and was involved in a number of ground-breaking events. He was a founding member of the Connemara Pony Breeders Society in Roundstone in 1924.

The same year he was selected to be chairman of the newly formed Irish National Fishermen’s Association.

He was also involved in encouraging industry wherever he went and was a tireless worker for the different parishes he served in.

It’s quite possible that given his later work at building schools and churches, the Archbishop sent him to Aran to assist Fr Farragher in building the new church in Cill Rónáin. This effort was formally launched in February 1902.

He died in Beckan near Ballyhaunis in 1935, a parish where he had built two churches.

But back to the battle between Fr Farragher and the Schoolmaster.

By March 1903, Pádraig Pearce had replaced Eoghan Ó Neachtáin as editor of the Gaelic League newspaper, An Claidheamh Soluis. The Aran Controversy undoubtedly played some part in this as many members were uneasy at Ó Neachtain’s confrontation with Fr Farragher.

It’s interesting that the Aran Islands played a very public role in two of the Gaelic League’s most famous clashes with church and state. In 1905 they took on the Postal Service with regard to the failure to deliver promptly, a letter addressed in Irish to a Cill Rónáin landlady.

We wrote about that controversy some time back and Mrs Gorham’s missing letter was raised in the House of Commons in 1905.

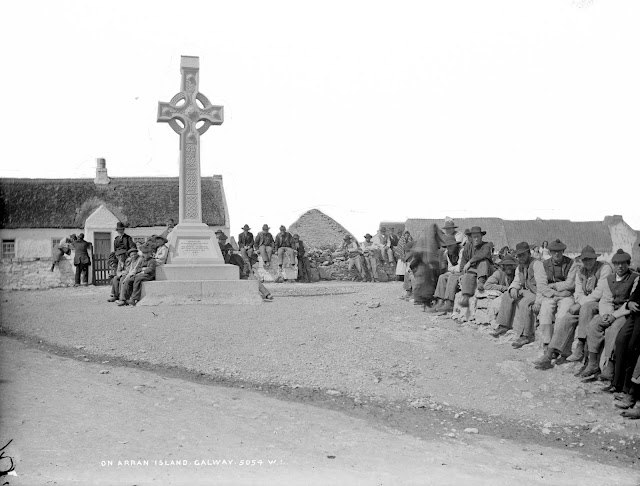

In 1905, Eoin MacNeill was writing to Pádraig Pearse about how the new church still hadn’t a proper altar. Pearse would have knowledge about this as his father James, was the stonemason who had recently carved and erected the magnificent Celtic cross, in front of the curate’s house in Cill Rónáin.

|

| Opened in 1905, one of Fr Farraghers many achievements. |

For the reasons outlined above it’s likely that O’Callaghan brooded at being treated like a servant and this may have come to a head when he refused to send a horse in October 1905 for Fr Farragher to attend the ‘Station’ at his house. (Some later reports of this incident say 1909 while others say 1905, which we think is the more likely)

He seems to have treated Fr Farragher with less that the respect a parish priest would demand in those days. The priest reported him and O’Callaghan received a caution from the Board of Education.

|

| Liam O’Flaherty modelled his character Moclair on Fr Farragher |

That the want of a horse caused such turmoil seems ironic when O’Callaghan lived just a stones throw from Gort na gCapall.

Shortly after arriving, Murtagh set up a very successful Agricultural Bank in 1898. The secretary of this farseeing enterprise was David O’Callaghan of Fearann an Coirce.

|

| The late, great Tim Robinson outside the old school residence at Móinín a’ Damhsa. Tim and his late wife Mairead lived here for many years while he compiled his famous map. (Photo Andrew McNeillie) |

Like Tim Robinson who came after him at Móinín a’ Damhsa, O’Callaghan was an avid collector of old yarns and also recorded unique Irish words, he picked up on the islands.

When the famous headhunters, Haddon and Browne visited the islands in the early 1890s, O’Callaghan gave them an incredible folk tale he had picked up from a man who claimed to have risen from the dead after two days.

|

| To be published in September 2023. |

(The academic and author Ciarán Walsh is an expert on the Irish Headhunters and we look forward to the publishing of his book, Alfred Cort Haddon, A very English Savage. in September 2023.)

O’Callaghan’s school residence was the centre of the Agricultural Bank operation. He would later write of buying this house from Fr Farragher for £25 in 1902, before all the trouble began.

Shorty after the horse incident in October 1905, Murtagh demanded David, hand him in the books of the bank. David refused as it was a Sunday and he had work to do on them.

Things were deteriorating quickly.

In his novel ‘Skerrett’, O’Flaherty had a character carrying untrue and distorted stories of what one man supposedly had said, in an effort to cause disharmony. It’s possible that there was an element of this in real life also.

When O’Callaghan started in 1885, the school had been mixed but this had changed in 1900 with the establishment of a separate boys and girls school. At the time, there were 105 boys and girls on the roll.

O’Callaghan now began to openly show his contempt for Farragher and visits to the boys school became very tense. There were claims that the teaching was not up to standard and that discipline was poor.

Both of the O’Flaherty brothers, Tom and Liam were fulsome in their praise for O’Callaghan but both remarked on how savagely he maintained discipline.

They admired his practical patriotism and love for the language, despite all the floggings he administered.

In Liam’s novel ‘Skerrett’ the priest introduced the teacher to his broken down school and unruly pupils with the words, …..“Here they are…..see what you can do with them….. I’ll stand for anything short of manslaughter”.

Following his return from America in the 1930s, Tom O’Flaherty wrote of his old teacher….

Mr O’Callaghan did great work. He was no cheap Jingo nationalist of the type that froths at the mouth at the mention of an Englishman; but he hated British imperialism and all its works and pomps.

There can be no doubting Fr Farragher’s commitment to his flock and like one of his many adversaries, the local doctor, Thomas Kean, contracted fever while ministering to the sick.

Fr Farragher would recover from smallpox in 1904 but Dr Kean died from typhus in 1901, leaving a wife and seven young children, the youngest an infant.

Fr Farragher was the manager of the school and so continued to visit. In the course of a later court case, O’Callaghen contended that Farragher conspired with some Board of Education inspectors to denigrate his teaching ability.

In February 1906 O’Callaghan was sick and the school closed for five schooldays. Because of this, he was docked £2-17-6. Fr Farragher had refused to believe that he was sick, despite a certificate from the islands doctor, Clareman, Michael O’Brien. O’Callaghan felt very aggrieved about this. It’s likely the doctor did too.

Dr Michael O’Brien had spent time in jail for his Fenian activities in Clare and had a close friendship with Liam O’Flaherty’s father, Mike. Both families were close and while Liam taught the O’Brien children how to fish and row a currach, the O’Briens taught Liam how to swim.

Dr O’Brien was a committed Parnell supporter and blamed the church for his downfall. Fr Farragher took a different view. For more information on the O’Brien/ O’Flaherty family friendship , here is a fine article by a descendant, Mary Jane O’Brien, from ten years ago.

Farragher was later described as ruling the islands with more authority than the Czar of Russia.

Schoolchildren are quick to assess a situation and O’Callaghan’s falling out with the priest would have undermined his authority and make maintaining discipline more difficult. Some of his pupils were teenagers, as tall or taller than himself. These older lads would only attend when the weather made fishing and outdoor work, impossible

On Farragher’s last visit to the school in March 1907 he instructed O’Callaghan to do something about the broken windows. When O’Callaghan correctly pointed out that as manager, that was his job, Farragher refused to sign the necessary documents.

|

| David O’Callaghan poses in 1906 with some of his pupils. From Jane W Shackleton’s Ireland 2012 by Christian Corlett (Collins Press) |

O’Callaghan now appealed successfully to the Archbishop in Tuam and shortly after, Farragher resigned as manager with the curate, Fr Michael J Owens, taking over.

Things seem to have settled down to an uneasy peace. This peace was unmercifully shattered by the fallout from a bombing incident on the night of June 1st 1908.

In July 1908, two men were convicted for bombing the priest’s house and committed to prison.

We wrote about this incident previously.

This bombing incident had nothing to do with O’Callaghan and was caused by a land and property dispute in Cill Éinne. Its aftermath however, would have a bearing on the row between Farragher and O’Callaghan.

After the two men went to jail, Fr Farragher, using the altar and the local United Irish League, ordered a boycott of the families of both men and of those who associated with them. This would cause much bitterness.

We wrote previously about the body of an English airman, Alfred Tizzard, being buried in Cill Mhuirbhigh in 1941. We remarked that Bryan Peter Stephen Hernon (1908-1987) defied Fr Killeen and buried Alfred in the local cemetery. The surest way to get Bryan to do something was to forbid him to do it.

It seems Bryan may have been following in the old teacher’s footsteps as in 1908, O’Callaghan, defied the priest and continued to associate with the families of the two bombers, Roger Dirrane and Matty Kilmartin.

He may well have regretted bowing to Farragher’s petty instructions to boycott the Connacht Feis in 1902 and determined not to bow down again.

On Roger Dirrane’s release from prison in 1910, relations with the priest deteriorated even further as O’Callaghan refused to shun him. This may have been more a defiance of the priest than a support of his past pupil, Roger Dirrane. We all like to pick our own enemies.

In truth, there was little sympathy on the island for Roger as his actions against the priest and his use of his teenage brother in law, were deemed cowardly and extreme.

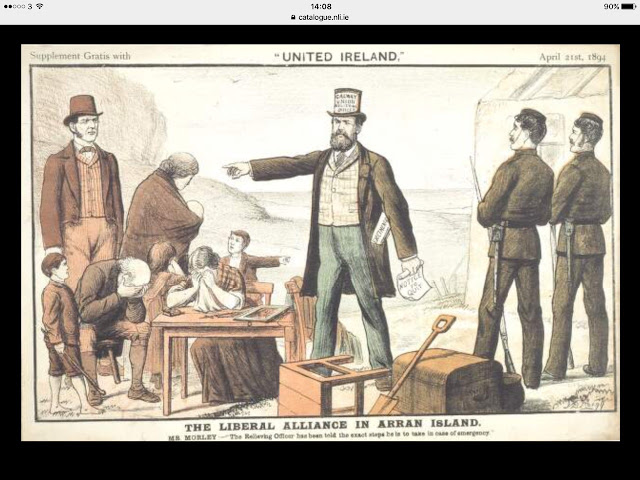

It was also only just over a decade since Roger was the bailiff on duty at the dreadful 1894 evictions. On that occasion more than 17 families, some of them his relations, had been evicted although most were reinstated later.

|

| A depiction of the 1894 evictions. London Illustrated News. (NLI) |

O’Callaghan continued to teach at his school. Tragedy however would strike David O’Callaghan in 1910 when his wife of thirty years, Bridget Laffe, died after suffering severe burns at their home when her clothes caught fire.She had lingered in agony for fourteen weeks but died on July 30th.

The school was set to resume on January 19th 1911 after the Christmas holidays. However, on the 8th of January at 11 o’clock mass in Eochaill, Fr Farragher had some strong words to say against O’Callaghan.

|

| From this altar in 1911, Fr Farragher encouraged parents not to send their children to David O’Callaghan. It would later lead to court proceedings by O’Callaghan for slander. |

These words, or more accurately a translation into English of them, would see David O’Callaghan taking an action against the priest for slander. We never could find out what exactly he said, in Irish.

The translation later heard in court in March 1912 was that Murtagh had said, ….

I would not recommend parents to send their children to that school if they had any other; not telling you not to send them there but if you take my advice you won’t. As you know, I have not visited the school for some time and when the priest does not visit the school, there is something out of place, and I believe the fault is not mine……

It‘s hard not to interpret these words as Fr Farragher speaking out of “both sides of his mouth” in claiming he wasn’t telling parents not to send their children to O’Callaghan.

Predictably, this resulted in no pupils showing up when O’Callaghan opened the boys school on January 19th, 1911. O’Callaghan continued to open the school every day for six months but his students never returned. By then his notice of dismissal had expired and his wages ceased.

By depriving him of his pupils first, Fr Farragher made issuing a dismissal notice much easier. While the curate Fr Owens was in theory his employer, Fr Farragher undoubtedly still called the shots.

In March 1911, O’Callaghan was refused confession by Fr Farragher on the excuse that he was associating with sinners. An extreme action for any priest to take and in conflict with the first lesson tiny children were taught, that we are all sinners.

Murtagh had previously refused a reference in 1906 for Michael O’Callaghan to attend teacher training college. An extreme interpretation of the biblical instruction of God of ……‘visiting the iniquity of the fathers on the children to the third and the fourth generation of those who hate me’.

|

| Fearann an Choirce school and teachers residence. |

Although the teachers Union did offer assistance to O’Callagher after he had lost his 1912 battle with Fr Farragher, in March 1911 he complained about his letters being ignored by the local union area representative in Barna.

It’s not surprising that the union was cautious about getting entangled in a row that involved the right of clerics to believe their sermons from the altar, enjoyed absolute privilege.

O’Callaghan closed up finally in June 1911 and shortly after, launched a slander action against Fr Farragher. He hoped to have the case heard in Dublin as he figured (correctly), because of Fr Farraghers deep involvement with the U.I.L, he’d have little chance if the case was heard in Galway.

It’s hard not to think that in 1911, taking a case against a Parish priest, for words said from the altar, was a foolish move. It’s likely that his solicitor had advised him against this action but it appears the whole mess had taken on an unstoppable momentum.

Murtagh had by this time an international profile and not just because of the bombing in 1908.

Murtagh was a charismatic man, well known for his progressive attitude and his opposition to Gombeenism which started with his Agricultural Bank in 1898. He had met with and was friendly with many people of importance and on June 10th 1911, he had played host when the Chief Secretary for Ireland, Augustine Birrell (1850-1933) and his wife Eleanor Locker, visited the island.

|

| Augustine Birrell, Chief Sec for Ireland Between 1907 & 1916 |

Fr Farragher’s vindictive boycotting was a major publicity coup for the Unionists as it seemed to confirm their famous slogan that ‘Home Rule is Rome Rule’. That nobody seems to have been able to convince the two antagonists to reach some sort of settlement, indicates just how bitter the dispute had become.

O’Callaghan had sued for £1,000 damages as his income and pension had been badly affected by his dismissal. Today, this would be equivalent to suing for about €170,000.

In June 1911, the court in Dublin moved the case to Galway and O’Callaghan was ordered to pay expenses. Legal costs would eventually destroy the man. O’Callaghan appealed this decision in July.

O’Callaghan must have known just how costly this course of action could entail. In the July 1911 appeal case where O’Callaghan failed to overturn the decision to move the case to Galway, he had employed one senior and one junior counsel as well as a team of solicitors. Fr Farragher had employed a similarly high powered team. The costs were mounting up.

|

| July 1911, O’Callaghan appeal to keep the case in Dublin is dismissed. It would be heard in Galway in March 1912 |

It seems that Fr Farragher’s difficulty was gaining sympathy for him on the island. The day after the original case being decided in June 1911, a man who was said to have been fired from his job with the CDB because he ignored the boycott and disparaged Farragher’s United Irish League, was assaulted in Cill Rónáin after being chased by a mob.

Shortly after O’Callaghan’s failed appeal in July 1911, Fr Farragher made the newspapers when he and his curate, Fr Owens, were hailed as heroes after courageously rescuing three Inis Oirr fishermen whose currach had capsized.

|

| After this, O’Callaghan’s chances of victory were severely dented. |

The writing was on the wall for a teacher taking on a famous hero. It’s hard not to wonder how a settlement wasn’t reached as another court case for Fr Farragher would surely destroy his receding chances of some day being made Archbishop.

From a religious point of view, the row was a cause of great scandal. However, it also had serious political implications. Farragher’s and O’Callaghan’s actions drew attention to the island.

In the House of Commons in London on May 25th 1911, the Unionist MP for North Antrim, Charles Craig drew attention to Fr Farragher and his use of the United Irish League to enforce his post bombing boycott. He would raise the issue again in July and November.

|

| Charles Craig 1869-1960. Older brother of James, the future N.I. premier. |

This apparent abuse of power by a Roman Catholic priest was used as an indication that the proposed ‘Home Rule’ would end up as ‘Rome Rule’

The case was finally decided in Galway before a jury of Galway’s leading citizens and Justice Hugh Holmes, on March 21st 1912. O’Callaghan’s fear that he would have no chance before a Galway jury would be confirmed in time. Fr Farragher’s strong connections to the United Irish League were of huge benefit, as those who didn’t support it were wary of it.

|

| Case heard before Justice Holmes. |

It is interesting to note who Fr Farragher employed in his defence team. Although he had been vilified in the House of Commons by Unionist MPs, his team included two committed unionists.

It was led by the Right Honourable Godfrey Featherstonhaugh (1858-1928) Kings Counsel and sitting Unionist Member of Parliament. Although Godfrey represented Fermanagh North, he and Murty Farragher were fellow Mayomen.

|

| The Mayo home of Godfrey Fetherstonhaugh K.C, M.P. Counsel for Murtagh Farragher in 1912 |

|

| Godfrey Fetherstonhaugh (1858-1928) |

Fr Farragher was a great admirer of Horace Plunkett, the father of the co-op movement. Horace had once served as a Unionist MP between 1892 and 1900.

He had visited Aran in 1898 and spoke highly of Fr Farragher’s efforts. He would eventually come to support Home Rule. It’s likely that Fr Farragher was familiar with politicians of all shades, as he lobbied for help for his islands parish.

Fr Farragher may have been impressed with Featherstonhaugh’s legal ability when he watched him successfully prosecute Roger Dirrane and Matty Kilmartin after they bombed his house in 1908.

Fr Farragher’s second Kings Counsel was a Sligo born Catholic Unionist, John Blake Powell. John would go on to be Solicitor General for Ireland in 1918 before becoming a Judge of the High court the same year.

In 1909, John Blake Powell, representing the Irish Unionist Associations, had lectured about the outrages and lawlessness encouraged in Connacht by Murty’s beloved United Irish League.

|

| Galway courthouse, where the case was heard in March 1912 |

While Fr Farragher had two senior counsel, one junior counsel and a team of solicitors, O’Callaghan would have had access to very limited funds and his team consisted of just two junior counsel and a firm of solicitors.

The implications of O’Callaghan being successful were very serious for clergymen of all denominations. For this reason, it’s likely that the priest had access to vastly greater resources.

In the course of his evidence Fr Farragher is reported to have denied saying the alleged slander. Strangely however, he also added that the words did not refer to the plaintiff.

The many conflicts were brought up and O’Callaghan’s teaching ability questioned. His continued association with the bomber Roger Dirrane was mentioned and also the fact that Roger had stopped attending mass.

This would not go down well with a Galway jury of rate payers and O’Callaghan was damned by association. Most of the all male jury of Galway’s leading citizens, were Roman Catholics but it included a Presbyterian and an Anglican.

Fr Farragher’s council highlighted how scandalous it was for a teacher to associate with a man who had bombed the priest. O’Callaghan denied being very friendly with Roger but that he occasionally met him at his sisters house.

In his evidence O’Callaghan listed out all the parish priests he had worked happily under, from Fr Concannon in 1880 and including Fr Michael O’Donohoe, Fr Peter McPhilpin and Fr Patrick Colgan.

He was very open about not sending a horse for the two priests in 1905. He admitted that he could have organised a horse if he wanted and that this was what islanders usually did.

For those unfamiliar with the old concept of a Roman Catholic ‘Station’ here is a good account.

|

| An account from Maureen Murphy’s Béaloideas Éireann article marking the centenary of the birth of Máire MacNeill in 1904. |

(There were no iPhones around in 1917 to capture a shot of the ‘Priest’s Breakfast’ at Winnie Folan’s house in Baile na Creige but if there were, we suspect it would be very impressive.)

In 1912, O’Callaghan declared that he didn’t have a horse and none of his neighbours had offered him one. He said the priests could have come by bicycle as they had done previously. It appears that Fr Owens had indeed arrived at the ‘station’ by bicycle.

|

| An advertisement from those times. |

|

| The priests were well used to cycling around the island as this piece from 1902 indicates. |

O’Callaghan also admitted that there had been negative assessments of his school in previous years.

Fr. Farragher’s counsel took grave exception to the depiction of the priest as follows…..… The defendant claimed the right to rule the island of Aran as absolute as any autocrat could have. He did not suppose that the Czar of Russia, in his own dominions was more powerful or autocratic a person than Rev Father Farragher in the Island of Aran…..

|

| Tsar Nicolas of Russia and his son, Alexi. |

Lord Justice Holme now put two separate questions to the Jury.

The first ……was the Plaintiff an unfit and unsuitable person to perform his duties as teacher of the Oatquarter Boys school in the Island of Aran…..

The second question was………did the defendant speak the words complained of in good faith and without malice towards the plaintiff………

The jury could not reach agreement about the first question but regarding the second, they accepted that Fr Farragher had spoken the words in good faith and without malice towards the plaintiff.

The case had opened at 10.30 am and concluded the same day at 7.30 pm. It was reported that the courtroom was packed with many ladies attending.

With the awarding of costs against him, David O’Callaghan must have known that he was now facing financial ruin as the costs of both legal teams would be his to bear. Recently widowed, his situation must have placed him under great stress.

On the evening of March 23rd, Fr Farragher arrived home to a tumultuous welcome at the pier in Cill Rónáin. While it has often been noted that Murty’s boycott and court cases split the island, it seems that Fr Farragher enjoyed the support of the vast majority.

|

| The pier where Fr Farragher was welcomed home in March 1912. Photo N.L.I. |

Fr Farragher was popular because his efforts had brought great benefits to the islands. His courage was also well known.

As a curate about twenty years before they had watched as he and a crew from the middle island battled a storm as he attended a sick call. This was before the telegraph was laid.

The Kilronan coastguards, watching through a spyglass, were sure that no boat could survive the terrible wind and waves.

For five stormy days over Christmas the islanders feared the worst but Fr Farragher and his crew had survived and he had spent a comfortable Christmas on Inis Meáin, enjoying dried fish for dinner.

|

| Launching a currach at Inis Meáin |

Fr Farragher was a great seaman and his faith in his currach crews and his God, resulted in him taking incredible risks.

David O’Callaghan appealed the Galway verdict but on May 11th at the Kings Bench Division in Dublin, his appeal was unanimously rejected. Once again, costs were awarded against him. This was the end of his legal road.

On May 20th 1912 an indemnity fund was set up on the island to help Fr Farragher with his legal costs, it being unlikely that the teacher could settle these debts. Money poured in from outside but the islanders themselves contributed to the fund also.

The papers published a detailed list of all those who contributed and more importantly, just how much they paid. It went from £2 down to the small sum of sixpence which was contributed by a widow in Cill Éinne who had a family of eight, the youngest being an infant.

It’s worth noting that a retired Church of Ireland policeman who had married Sarah, daughter of Chard the shopkeeper, contributed half a crown to the Farragher fund. We came across his father-in-law Thomas Blake Chard (1827-1913) when we covered the famous 1868/69 sectarian ‘Aran Bread War and the Stolen Children’

The teachers Union on the mainland also got involved and resolutions encouraging contributions to O’Callaghan’s costs were passed in many counties.

We can find no published list of the teachers who contributed to the indemnity fund for David O’Callaghan. This is not surprising as being publicly named as a contributor could give rise to serious repercussions.

However, the teachers on the island, for the most part, supported Fr Farragher and the two secretaries of his indemnity fund were National School teachers.

Fr Farragher had O’Callaghan back at the Kings Bench Division in June 1917 where his means were examined.

Despite the sale of his house, his cashing in of some £20 in shares he had in Galway Woollen Mills, the money donated by fellow teachers to help him, along with the indemnity fund raised for Fr Farragher, he still owed the priest £200.

This seems hardly credible but of course, going to court was always an expensive business. Also, Fr Farraghers indemnity fund would only need to be used, after all other avenues were exhausted

O’Callaghan had a pension of £53 a year and £10 in the bank which his daughter Máire had given him for a holiday. His insurance policy of £300 would mature in a few years and Justice Gibson alerted him (deliberately or not) to having this assigned. This did not go down well with the examiner. We can only hope that O’Callaghan, taking a cue from Justice Gibson, did indeed assign his insurance policy to his daughter or son.

The whole examination must have been very humiliating for O’Callaghan as both Judge Gibson and the examiner tried to outdo each other in their attempts at condescending humour.

An interesting fact about Justice John George Gibson is that he presided at a famous case in 1905 about a name in Irish on an ass-cart in Donegal. We covered this briefly when writing about Mrs Gorham’s missing letter in the same year.

Justice Gibson was the uncle to a very committed Gaelic League supporter, the 2nd Baron Ashbourne, William Gibson. William’s sister Violet would later attempt to assassinate Benito Mussolini in 1926. An interesting family, to say the least.

It’s likely that the publishing of parishioners names and amounts in 1912 for Fr Farragher’s indemnity fund resulted in almost the entire island contributing, willingly or not.

It reminds us of a story an old man once told us of attending mass long ago on the mainland in Co Clare. The priest read out who had contributed their Easter dues and added how much. This list gave you an idea of where you stood in the parish social order.

When the priest had read down to the names of those who had paid a shilling, he was expected to conclude as this was usually the minimum.

However, after a short pause he continued on and called out the name of an aging bachelor who enjoyed socialising.

After a dramatic pause he solemnly declared… Nothing. He followed this up after another pause with the words…. And nothing last time.

This was too much for the man in question who jumped up in his seat and shouted ….And nothing next time either Father.

The repercussions for O’Callaghan were severe and his house was sold to help pay the costs. He claimed to have spent £15 improving it and complained to the paper in December 1913 that his house had been sold and he was facing homelessness. It’s likely that the named buyer, Mate Folan, was acting on behalf of Fr Farragher and the parish in buying back the school residence.

The final act came in January 1914 when O’Callaghan was evicted and his thirty four years on the islands came to a sad end.

At the end of the day the only people who benefited from the affair were the lawyers and it’s likely that Fr Farragher regretted how things had deteriorated.

Given the disparity in funds and esteem, David O’Callaghen should never have taken the case. However, by taking the case he had fired a shot across the bow of any priest or minister who thought he could say what he liked from the altar.

This lesson was not absorbed by some priests that came after him as some older islanders living today can testify to.

Battles between Schoolteachers and Parish Priests were widespread up until relatively recent times.

Just a few years after O’Callaghan’s eviction, accusations were made of a priest using the altar to slander a schoolteacher. This was just across the North Sound in An Ceathru Rua and the stress may well have contributed to the teacher dying in 1920 at the age of fifty.

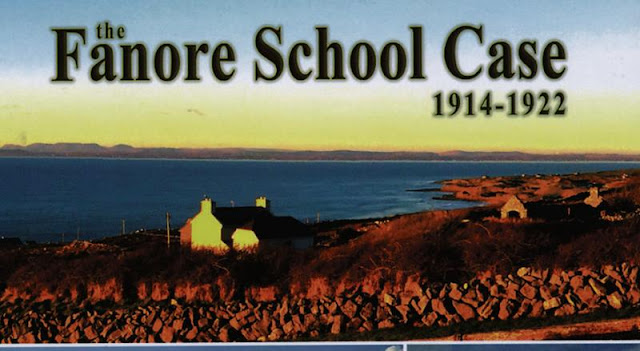

Also, in 1915 in Fanore in West Clare, an angry parish priest, summarily dismissed a schoolmaster, allegedly over his choice of wife. The row that followed was documented in Joe Queally’s 2004 book The Fanore School Case

Joe is a local historian who has published a number of books. He is also a great supporter of the Lifeboat Institution.

RTE made a programme about this case in 2004. While it has many similarities with David O’Callaghan’s clash with his Parish Priest, one significant difference is that over seventy percent of the pupils kept attending Fanore school.

|

| Joe Queally’s 2004 book |

Fr Farragher left the island for Athenry in 1920 where he had his house there raided by the Black and Tans about the same time that they raided the island.

Fr Farragher died in 1928. He had been very ill for some time but had held on until shortly after his mother died, thus sparing her a great sorrow.

Some weeks later his effects were sold at auction and it is sad to see the worldly goods of such a great man, from his De Luxe Overland car to his 4 valve wireless and domestic implements, listed for all the world to see.

|

| Overland Advertising in 1924 |

His legacy on the islands is mixed. He was a powerful advocate for progress and we detailed some of his many Schemes and projects when we wrote about him being bombed.

The bitterness from the boycott would last for many decades and is still talked about today but Murty Farragher’s net contribution to the three islands development was immense, despite his tendency to demand absolute subservience.

While O’Callaghan’s legal team might have been losing the run of themselves when making the reference to Murty and the Czar of Russia, in many ways they were correct.

David’s daughter Máire ní Cheallacháin, went on to a distinguished career as a teacher and writer. Her 1922 phrase books ‘Irish at Home’ and ‘Irish at School’ are credited with instilling in many, a curiosity for the language.

|

| Irish at School by Máire ní Cheallacháin (From Boston College Library) |

Máire was on the teaching staff of the original Scoil Bhríde on Stephen’s Green when founded by Louise Gavan Duffy and Áine nic Aoidh in 1917.

Previous to this she had spent two years teaching Irish at the Loretta convent in Balbriggan. During her time there, Scoil Bhríde was raided during the war of independence and ransacked on one occasion.

In 1944, Máire succeeded Louise Gavan Duffy as headmistress at Scoil Bhride and held this position until 1950. There may still be a few of her past pupils alive today.

What became of Michael O’Callaghan, we don’t know but he was said to have emigrated to Australia.

It’s almost certain that without David O’Callaghan’s influence, the writers Liam and Tom O’Flaherty would have had a very different life path. Both men were radicals and it’s not every teacher can point to two past pupils who were founding members of Communist parties. Liam in Ireland and Tom in the United States.

O’Callaghan had highlighted the benefits of having a native Irish speaker enrolled, to convince different secondary schools to offer scholarships. His own children were successful at gaining entry as was Liam O’Flaherty and others.

His contribution to education through Irish in both Árainn and Ireland was significant and his school at Fearann an Choirce led the way nationally in encouraging the use of Irish in Gaeltacht districts. .

David O’Callaghan would make one last visit to the islands in 1931 and he died in the Workhouse/County Home at Newcastle West, Co. Limerick in 1937, aged 75.

|

| The County Home in Newcastle West Co Limerick. (Photo Newcastle West Olden Times) |

|

| Funeral of Canon Farragher in 1928. Photo Connacht Tribune |

David O’Callaghan and Murty Farragher had a common goal in promoting both the welfare of the islanders and the preserving of the language. While both were progressive, Fr Farragher appears more conservative in his politics, while O’Callaghan leaned heavily towards socialism.

Both men had seen the recurring distress and appeals for help during their years on the islands. Like Michael Davitt, they recognised that the only remedy was social/political reform and to develop a self-help mindset.

The Agricultural Bank was part of this and after O’Callaghan had left, Fr Farragher founded the Cill Mhuirbhigh fishing Co-op in 1915. This was to combat fish buyers who were working together to deflate prices.

O’Callaghan, along with Murty’s immediate predecessor, Fr Patrick Colgan, had been instrumental in the formation in Cill Rónáin of a CDB backed fishing Co-op in the 1890s.

O’Callaghan had helped fishermen too poor to buy a boat, by renting two currachs out. This gave employment to six or eight men.

|

| Fishing Co-op founded in 1915. It folded after Murtagh leaving in 1920 and a collapse in fish prices. |

It was a tragedy that these two men couldn’t work together and that they allowed personal antagonism to damage both their lives.

Both men had a deep commitment to saving the Irish language but while Fr Farragher had the benefit of a bilingual upbringing, O’Callaghan had but a few words when landing on Inis Meáin in 1880.

We will leave the last words to the writer Tom O’Flaherty (1889-1936) who said of his old teacher………. He was a fine man. How many workers like O’Callaghan are forgotten when the ideals they struggled for are realized in whole or in part, while the blatant politicians and the gentlemen who always manage to pick the winning side, are honoured.

|

| The deserted schoolyard at Fearann an Choirce. The playground for generations of schoolchildren. |

|

| All that remains today of the spot where David O’Callaghan once taught his little school. |

Michael Muldoon April 2023

(We have tried to be as accurate as we can but if we have been incorrect in relevant facts, we welcome all contributions.. Opinions, our included, are two a Penny but facts are priceless.)

No comments:

Post a Comment