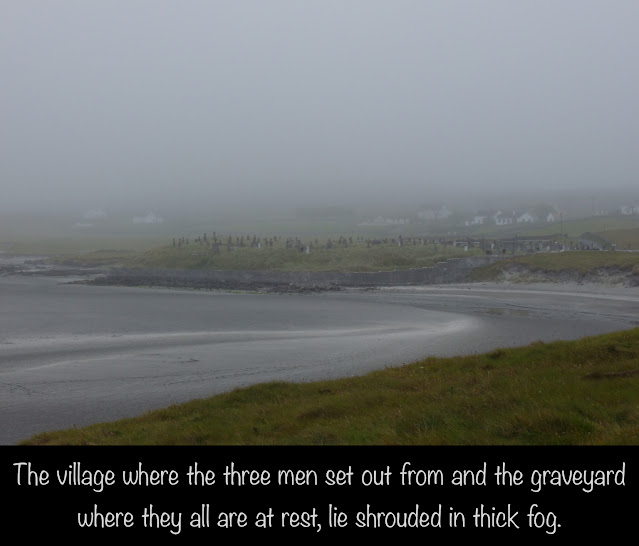

The writer Liam O’Flaherty (1896-1984) from Gort na gCapall had the dubious honour, in 1930, of being the first Irish writer to be banned under the new ‘Censorship of Publications Act’ of 1929. He would not be the last.

|

| Liam O'Flaherty |

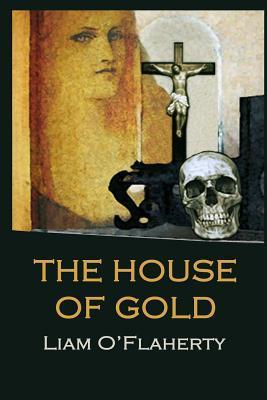

His Galway town novel ‘House of Gold’ was listed with other publications in November 1930 as being a danger to public morality. It was published the year before, in October 1929, but not included in the first round of thirteen banned books, in May 1930.

It was not banned during the first round as it was already in the book shops and the authorities feared (probably correctly) that by banning it, there would be a rush to buy it before stocks ran out.

It was hoped that it would be withdrawn voluntarily by the book shops before it was listed as being banned.

Self censorship, particularly of newspapers, was one of the intended outcomes of the censorship act. It became a stick to wave over the heads of newspaper editors and book sellers, for decades.

The 1929 censorship act must have been the cause of many manuscripts being rejected by publishers who couldn’t take the financial risk of them being banned.

The myth went around that being banned was good for a writer’s reputation. The only real benefit was in the six counties of the North, where a display saying 'BANNED IN FREE STATE' was often used to promote sales.

|

| Irish Times |

|

| The free-thinking dancer Isadora Duncan, whose book ‘My Life’ was also banned in 1930. |

Also listed that day was the autobiography ‘My Life’ of the scandalous and tragic dancer and feminist Isadora Duncan (1877-1924). Isadora was Irish/American and deemed by some to be an embarrassment to Irish womanhood. This would have added to the reasons to have her banned. She had been killed in a car accident involving her scarf getting caught in a wheel in 1924.

While it is often mentioned that the Free State government was dominated by narrow-minded, arch conservatives, the orgy of banning did not end with the election of de Valera’s government in 1932.

In 1942, Dev’s censorship board banned Eric Cross’ book The Tailor and Ansty.The book was a humorous but earthy report on the incredible turn of phrase of an elderly Cork couple, Timothy Buckley and his wife Anastasia McCarthy.

|

| Banned in 1942 |

Cross detailed the humorous and insightful type of conversations rural people might engage in occasionally within earshot of, perhaps, the curate but most definitely not, the parish priest.

After it being banned, the Tailor and Ansty were terrorised by local hooligans and many neighbours shunned them.

Over eighty years later, it is still a matter of shame that three parish priests arrived at their home and forced the elderly tailor, on his knees, to burn the book that he was so proud of.

In fairness, some other priests were outraged by this bullying of Timothy and courageously supported both Eric Cross and the elderly couple.

|

| Banned in 1930 but republished by Nuascéalta in 2013. |

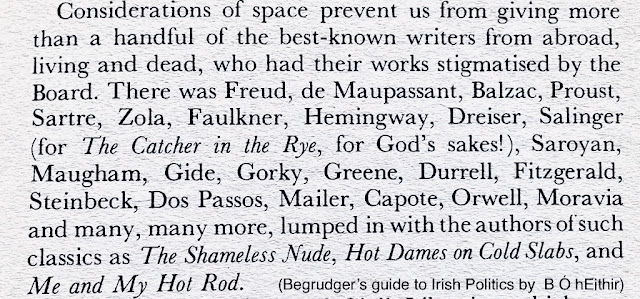

The late Bredán Ó hEithir had a great sense of humour and once noted how ridiculous it was to see some of the world’s greatest writers being listed beside titles of a more lurid and explicit nature.

|

| From Brendán Ó hEithir's 1986 book 'The Begrudger's Guide to Irish Politics'. (Poolbeg) |

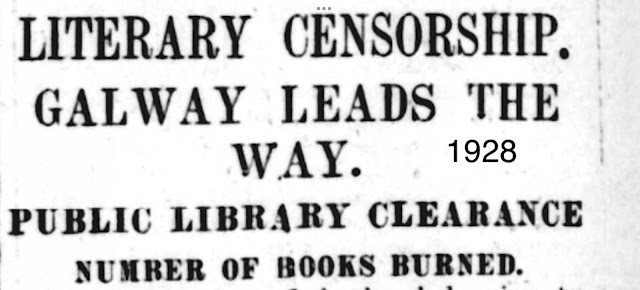

While 1929 saw the enactment of censorship laws, it would be a mistake to think that this was the start of post-independence literary vandalism.

In 1928, rumours began to circulate that books belonging to the Galway County Library, some having been donated by the Carnegie Trust, had been burned between December 1924 and February 1925. This was done on the instructions of the official Galway Library censor, the Archbishop of Tuam, Thomas Gilmartin.

| Thomas was also involved in the Mayo Library controversy of 1930 over the appointment of a Protestant librarian. |

How Archbishop Gilmartin and his army of agents, both lay and clerical, avoided moral depravity from having to check books for immorality, God only knows.

A favourite pastime for many lay zealots was to descend on libraries in a righteous hunt for offensive words. They would then submit a book to harassed librarians and the authorities, with all the ‘dirty bits’ highlighted.

The writer Frank O’Connor, (Michael O’Donovan) worked as a librarian and was once confronted by a young man who objected to an indecent word he had found. Turned out the indecent word was ‘navel’.

O’Connor felt sympathy for the young man’s ignorance but not as much as he felt for any young woman who might end up with him.

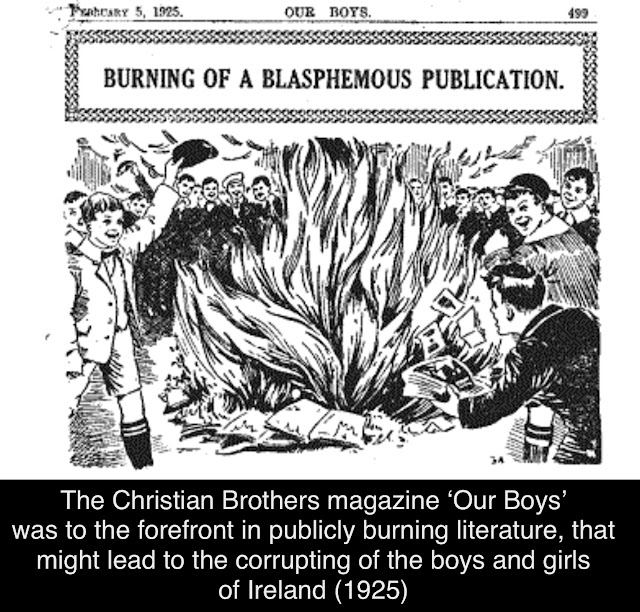

Protecting the innocent minds of the young was deemed sufficient reason to burn with enthusiasm. The Tuam-born editor of the magazine ‘Our Boys’, Brother Canice Craven, led the way in this crusade.

The Galway book-burning rumours came to a head in October 1928 at a meeting of the Library committee.

Councillor and former Labour TD Gilbert Lynch asked about the alleged book-burning. He also pointed out that as a censorship bill was about to be enacted, there was no longer any need for Archbishop Gilmartin to act as censor.

Lynch knew a fair bit about the Archdiocese of Tuam as his Mayo grandmother, Bridget Egan, was very proud of being a first cousin to the famous Archbishop John McHale (1791-1881).

|

| Gilbert Lynch and his wife Sheila O'Hanlon From Aindrias Ó Cathasaigh’s 2011 book 'The Life and Times of Gilbert Lynch'. (Sourced at Irish Labour History Archive) |

Lynch inflamed feelings even more by pointing out that the Archbishop of Tuam wasn’t infallible. This may have been news to some of those present.

Not surprisingly, this met with fierce resistance from one of the clerical representatives on the committee. This was Fr James O’Dea (1894-1971), private secretary to Thomas O’Doherty, the Catholic Bishop of Galway.

There was already an Index of Forbidden Books which all Catholics were prohibited from reading but the Galway County Library committee was, in theory, non denominational and secular.

|

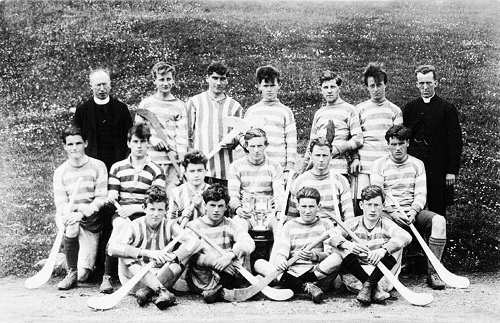

| James O'Dea as a young priest, with a St Mary's college hurling team in 1924. From Galway Diocesan magazine of 1959, 'The Mantle'. |

A month or so later, after much ridicule and strong reaction to the book burning, the Library Committee listed the criteria under which the restricting and burning took place.

It stated: Treatises on philosophy and religion which were definitely anti-Christian works.

Novels destroyed were those that displayed:

1. Complete frankness in dealing with sex matters.

2. Insidious or categorical denunciation of marriage or glorification of the unmarried mother or the mistress.

3. The glorification of physical passion.

4. Contempt of proprieties and conventions.

5. The detailing and the stressing of morbidity.

It’s obvious that such subjective and vague criteria as above gave incredible power to ban almost anything. It seems that the only passion to be tolerated was that of a religious nature.

It’s important to point out that arrogance and righteousness was not confined to just the Library Committee in Galway.

In 1927 a meeting of the governing body of the recently extended Central Hospital detailed how the name and address of every unmarried mother who gave birth there was furnished to the hospital chaplain, Fr Davis.

|

County Galway Hospital & Dispensaries committee archive 9th Feb 1927 GC6/6 page 7 Galway County Council Archives. |

The job of the hospital chaplain was to pass this information on to the home parish priest of every young woman or child/woman. The hospital committee even went so far as to record the number of illegitimate births from different parts of the county but showing sensitivity by leaving out the mothers’ names.

Sad to have to say, but the reason why unmarried mothers were being held in Loughrea until just before birth was that there was strong resistance by married mothers to sharing a ward with them at the Central Hospital in Galway. This had caused a mini boycott of the maternity unit there.

And here we must declare a possible bias against Fr O’Dea of the 1928 library committee. He was a very staunch GAA man and served for decades in senior positions to the Galway County Board. He was finally unseated in 1971, in a stunning defeat by an old adversary, Gort native Stephen Carty of Dominick Street in Galway.

In 1938 he confronted my father as he waited to attend the hurling final between Castlegar and Maree outside the Sportsground on College Road. He accused him of attending a rugby match. My father was an outstanding hurler but was suspect as he had played rugby in his school days at Garbally College.

|

| County finalists in 1938 (Connacht Tribune). |

There had been a junior rugby match on earlier that day as the ground hosted both codes in those times but my father hadn’t in fact been attending it. He explained this to Fr O’Dea and thought that would be the end of the matter.

(We tried, but failed, to resist mentioning what a famous Rugby International from Kerry once noted. He figured that club rugby was a bit like pornography, frustrating to watch and really only enjoyed by those taking part.)

My father was angered that his word was not enough for Fr O’Dea and very annoyed when he got a letter telling him to attend a meeting and explain why he should not be suspended. Typical of the man, he wrote back declining the invitation and spent a number of years outside the GAA fold playing rugby with Loughrea.

He returned eventually to his first love, hurling, playing on the losing Killimor team in the county final of 1944 against Castlegar.

Younger readers may be surprised to know about the vigilante committee of those days which kept tabs on the attendees at “foreign” games and dances. Suspension followed for any who were adjudged to have broken the rules.

This rule caused much controversy in Galway Town where, as Brendán Ó hEithir pointed out in his landmark GAA book ‘Over the Bar’, the only foreign game was gaelic football and where hurling, soccer and rugby dominated.

As we have started down this boreen we may as well add this humorous story about ‘The Ban’ before we go back to the book burning.

In the 1960s, a member of the vigilante committee regularly placed himself outside the Sportsground in order to note errant GAA men coming out after a rugby match.

At the time, the late Seán Conneely of Cill Muirbhigh was an outstanding player and very much part of the rugby scene in Galway.

|

| Seán Conneely (with the ball) on an Árainn football team of the early 60s. |

A Cill Muirbhigh neighbour of his and powerful gaelic footballer often attended Seán’s matches. Pretending to know nothing of 'The Ban', he would walk across the road to the man putting names in a notebook and innocently start a conversation with him, in Irish.

The pressure of having to respond, causing a distraction, his many GAA friends coming out behind him pulled down their caps and pulled up their collars while making a speedy escape.

But back to the 1928 book burning meeting.

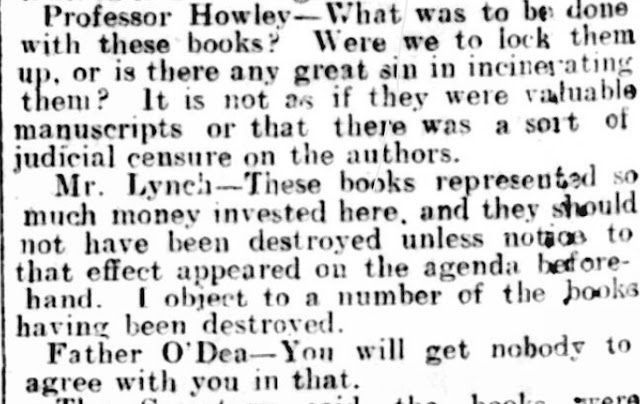

Fr O’Dea was supported in the Archbishop’s right to burn books, his refusal to give the committee a list of the books burned and, in particular, O’Dea’s lack of confidence in the new censorship bill, by the Chair of Philosophy at UCG, Professor John Howley (1866-1944). John was also the University College Galway librarian.

|

| Justifying book burning in 1928. |

While not going so far as to endorse book burning, the local Presbyterian minister, Andrew Gailey (1896-1963) seems to have shared Fr O’Dea’s lack of confidence in the new bill.

Not surprisingly, Lynch got little support although the committee chairman, Eamonn Corbett, did attempt to have a list of burned books made available to the library committee.

He was supported by Councillor Peter Kelly who objected to selective members withholding information from the full committee.

In this, they were overruled with Professor Howley making derogatory remarks about the ‘intelligentsia’. Obviously not a group the Professor of Philosophy would like to be associated with.

Lynch himself was suspect in clerical eyes for a number of reasons. He was a Lancashire-born and raised Irishman, who was involved in arms smuggling and fighting in 1916 in Dublin.

Those taunting him about his English accent were soon quietened when reminded that Gilbert had stormed the GPO in 1916, revolver in hand, as Pearse and Connolly made their move.

His wife Sheila O’Hanlon was even more involved in the 1916 rising as a leading member of Cumann na mBan.

Gilbert was very much a Connolly-admiring socialist who worked as union representative and what made him difficult to dismiss as a Godless, Bolshie, Communist was that he was a very committed Roman Catholic.

|

| Gilbert Lynch. Born Stockport in 1892. Died in Dublin, 1969. (Sourced at Irish Labour History Archive) |

Elected as a Labour TD for Galway County in June 1927, Lynch served for less than three months before losing his seat at the September general election, triggered by the assassination of Kevin O’Higgins.

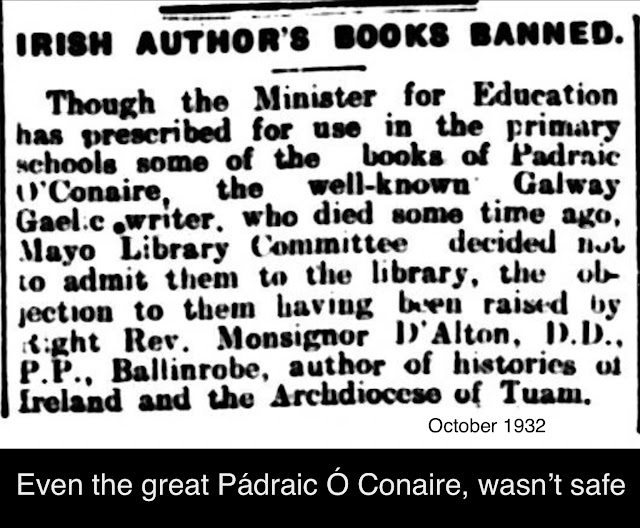

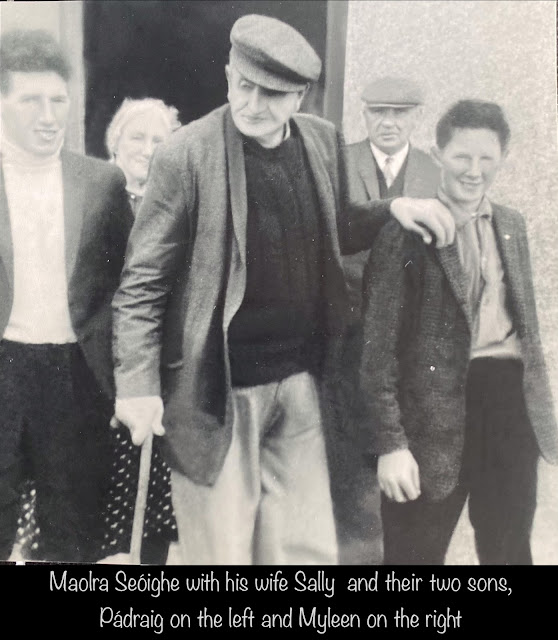

The writer Pádraic Ó Conaire campaigned alongside Gilbert in Connemara and against his own cousin, Máirtín Mór McDonogh of Cumann na nGaedheal. Máirtín Mór was elected in both June and September. The whole of County Galway was then one constituency with nine seats.

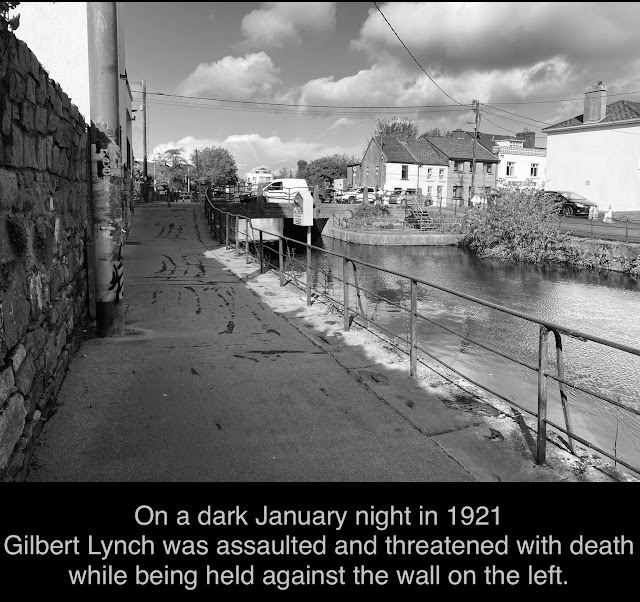

Lynch first arrived in Galway in late 1920 as secretary to the ATGWU and after being dragged from his lodgings at St John’s terrace, came near to being murdered by mysterious men with English accents.

These men were probably Black and Tans but he wouldn’t have been the first Union organiser to be encouraged to leave an Irish town at the behest of the bosses. He left town shortly afterwards, returning in 1925.

|

| Gilbert considered diving into the canal and swimming underwater for the swing bridge on New Road. He was a powerful swimmer but figured the risk was too great. |

This was not Lynch’s first brush with violence as apart from his exploits in 1916, he had been subject to rough handling during his Trade Union activities in Manchester.

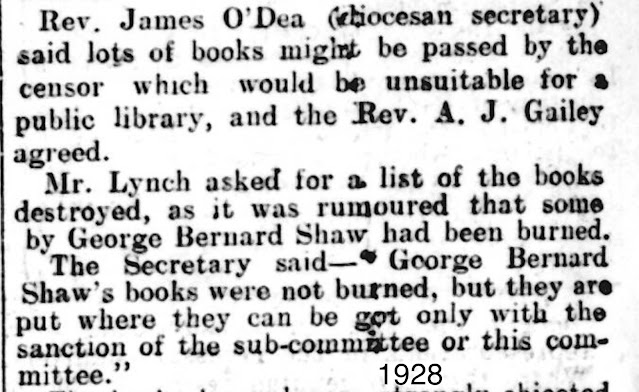

It was believed that books by Leo Tolstoy, George Bernard Shaw, Benedict Arnold and Victor Hugo were among the books burned. The flames of hell being kept at bay by the flames generated by ‘dirty booooks’.

Fr O’Dea said that it was nobody’s business as to what books were burned. He didn’t realise that Lynch was walking him into a trap when innocently asking if books by a popular Catholic author in America, Peter B Kyne, had been burned. Lynch of course suspected that they hadn’t.

Feeling confident, Fr O’Dea assured the committee that no Kyne books had been burned but by confirming this, his refusal to confirm or deny was revealing, when Lynch asked him subsequently about certain other writers.

Fr O’Dea was forced into denying that Shaw’s books had been burned but admitted they had been removed and could only be accessed with special permission. He also cringingly added that none of Tolstoy’s books were fit for circulation.

Many people are familiar with a humorous/sad but probably untrue story about Shaw and the dancer Isadora Duncan, whose autobiography was banned with Liam O’Flaherty’s ‘House of Gold’, in November 1930.

After the tragic loss in 1913 of her beloved children, Deirdre (6) and Patrick (3), the unmarried and free spirited Isadora is alleged to have asked Shaw if he would father a child with her.

She was reported to have suggested that a combination of her beauty and his brains would “startle the world”. Shaw gently refused with the words “I must decline your offer with thanks, for the child might have my beauty and your brains” .

(It’s likely that the story was invented, as Shaw was unlikely to be so cruel to a fair lady. He later denied it ever happening. A similar story did the rounds also, where the man who declined a request was Einstein)

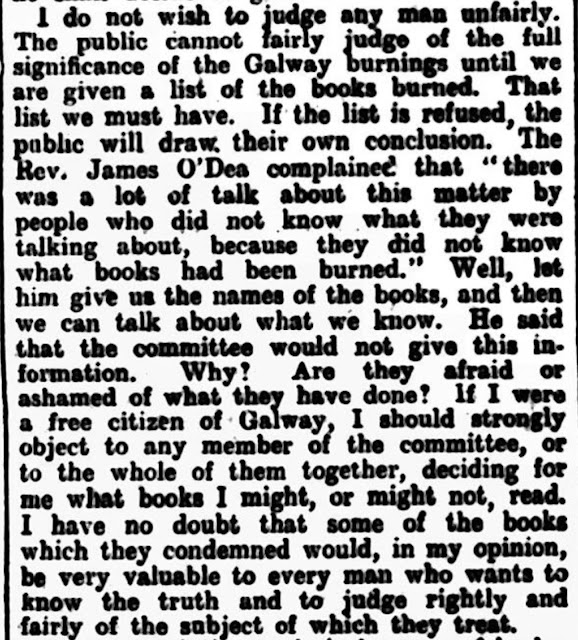

Shaw would later make a withering comment about the banning and burning of books by Galway Library committee and the soon to be enacted censorship legislation.

Gilbert Lynch clashed regularly with one of Galway’s most famous characters and biggest employers, Máirtín Mór McDonogh. Máirtín’s mother was Honoria Hernon from Aran. His uncle was the Aran Islands bailiff, Bart Hernon, for whose attempted murder Bryan Kilmartin was unjustly jailed in 1882. Máirtín Mór McDonogh was a cousin to the Gilbert supporting writer Pádraic Ó Conaire.

It’s likely that Máirtín Mór had even less time for Liam O’Flaherty as it was common knowledge that his banned novel 'House of Gold' was loosely inspired by the McDonogh dynasty. A poor regard for O’Flaherty was shared by government minister Desmond Fitzgerald, father to the more tolerant Garrett.

The matter of the book burning was raised in the Dáil which resulted in many politicians ducking for cover and kicking for touch, in case they might upset the Archbishop or get what was metaphorically known as ‘a belt of the crozier’. This could be politically fatal.

Following the revelations at the library committee meeting, many letters to the paper were scathing in their criticism, with Galway Library Committee becoming a laughing stock.

In particular, there was annoyance when Fr O’Dea dismissed the controversy as “people talking about something they knew nothing of”. This, after he refusing point blank to give a list of the books burned. One contributor to the debate was the Carlow-based Anglican Minister, Rev Dudley Fletcher, a serial letter writer of his day.

|

| A small part of Rev Dudley Fletcher's letter to the papers. |

Liam O’Flaherty was not the only writer with strong Aran connections to find himself banned. Brendan Behan was a regular visitor to the islands long ago and saw his great book 'Borstal Boy' banned in the 1950s. The pioneering writer from across the sea in County Clare, Edna O’Brien, was similarly banned and indeed had her books burned in 1960.

While Fr O’Dea and Gilbert Lynch clashed over book burning, they had similar views about foreign games. In 1929, Gilbert supported a motion at Galway County Council that schools that played rugby should be barred from participating in council scholarship schemes. Just one councillor, Peter Kelly of Turloughmore, opposed the motion.

After leaving Galway in 1931, Gilbert went on to be President of the Irish Trade Unions Council. In 1945 he met Charles De Gaulle in Paris.

He told Lynch that he had great grandparents from Co Cork. Lynch remarked that this explained his refusal to bow down to Hitler.

De Gaulle was not impressed as he regarded himself as the embodiment of France and his obstinacy of Gallic rather than Gaelic origin.

It’s all in the distant past now and we must factor in that people were conditioned by the times they lived in and how society viewed itself.

We must also remember that there were undoubtedly underlying tensions within the committee, as this was just five years after a vicious Civil War.

In many ways, scapegoating Fr O’Dea and the Archbishop obscures the most shocking aspect of the whole affair. After all, they were just defending and reinforcing the dominant position of their church.

It’s disappointing to think that there was only one man who objected to the library committee’s actions. They were mandated by duly elected councillors but were prepared to give absolute power over what books the people of Galway could read, to the unelected Archbishop of Tuam.

This extended to the committee endorsing Fr O’Dea’s view, that asking for a list of books burned would be insulting to the Archbishop. It appears that the committee was fearful of upsetting the prelate.

Not only were the people of County Galway denied the right to read certain books, they were denied also the right to know which books they couldn’t read.

However, it’s reassuring to know that during the book burning controversy of 1928 there was a man like Gilbert Lynch who was prepared, with little or no support, to call out this deferential cowardice.

The man with an English accent who could ‘talk for Ireland’.

Michael F Muldoon. October 2022.

(The Life and Times of Gilbert Lynch, edited by Aindrias Ó Cathasaigh and published by The Irish Labour History Society.)