Draft 4

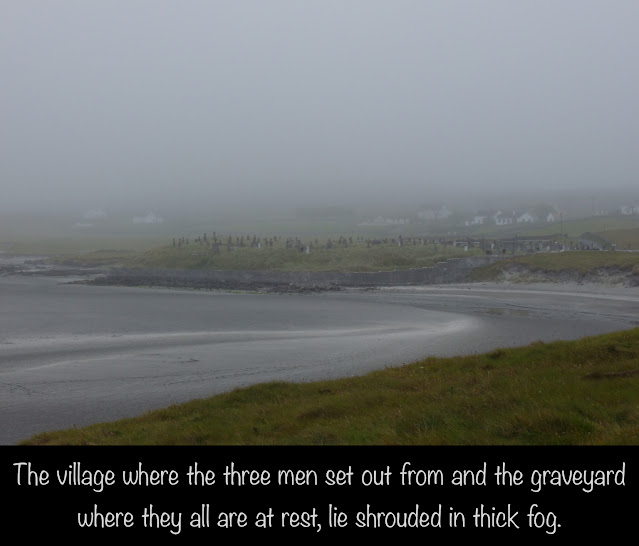

Death on Galway Bay.

The winter storms that are a constant feature of West of Ireland life had been battering the Aran Islands during the Christmas season of 1927. A break of a day or two was not unusual but in a time before highly accurate weather forecasts, venturing out for a spot of fishing was always fraught with risk.

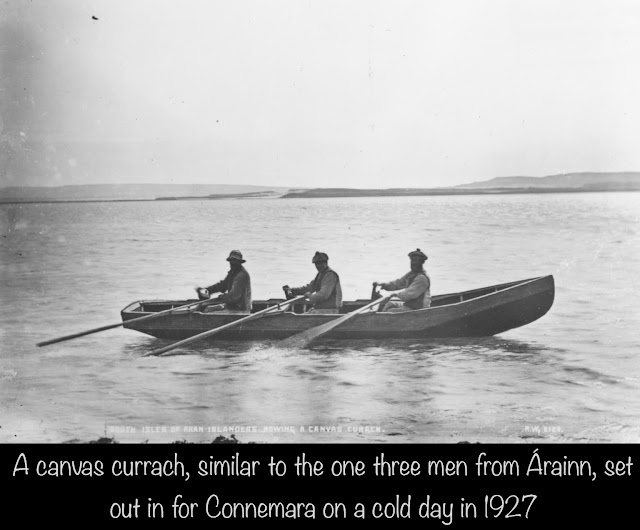

A break in the weather persuaded three Iaráirne men to head out to sea at 6am on the morning of Friday December the 30th, 1927.

It was dark when the three men lifted their currach from its ‘frapaí’ among the sand dunes above Trá na Ladies and carried it down to the sea. This sandy shore runs parallel to the main runway at Cill Éinne airport. They would not have known how long they would be out as this depended on how much herring they would find in their drift net.

Cuan Chill Éinne was a great spot for herring in those years and small boats had a good chance of making a big haul in the sheltered bay. Currachs had a distinct advantage when the herring moved into shallow waters, close to land. Many islanders can still remember carts loaded with herring heading across the island in the 1950s, selling as they went.

The three men who set out that morning were Pat Conneely aged forty eight and married with eight children, Michael Burke aged twenty seven and married with three children and the unmarried Maolra Seoighe (Myles Joyce) who was aged thirty two. Both Pat and Michael had an infant child at home.

Their good luck in striking a fine shoal would by outdone by much bad luck as the whole expedition turned to disaster. By 9am they had caught around three thousand fish and decided to head for Connemara and sell their catch. In view of the bad spell of weather over the Christmas, fresh fish would be in short supply all around the coast as many boats were tied up in harbour.

The need to row to Connemara would have been unnecessary a few years previously, after a very helpful island fishing co-op had been established in 1915. Then, fishermen were guaranteed sale for their fish but this experiment collapsed after the return of British boats post World War 1 and after the founder, Fr. Murty Farragher, had been transferred to Athenry.

|

| (Many thanks to John Bhaba Jack Ó Conghaile) |

It’s likely there was a glut of herring for local consumption, which prompted the three men to head for the mainland. While large quantities were home salted in barrels, there was a limit to local demand.

Newspapers reported that giving evidence some days later, Myles Joyce recalled how it had taken them until 4pm to reach Connemara and sell their fish. This newspaper report is probably incorrect, as even with such a large amount of fish and wet nets, a currach leaving Árainn at 9am, with three experienced oarsmen, would have made the crossing before or shortly after midday.

|

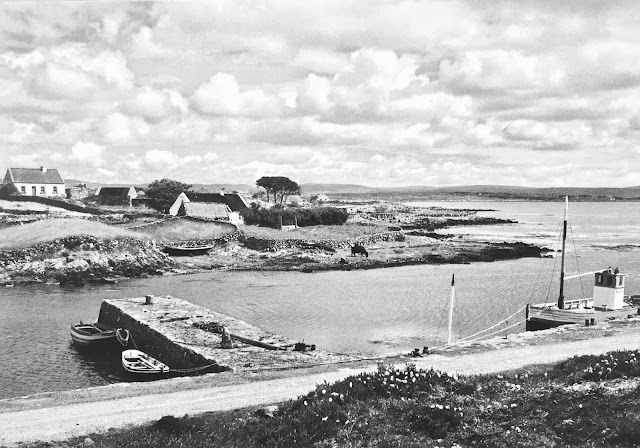

| Sruthán Pier in the 1990s. (John Hinde) |

They came ashore at Sruthán pier which is about a mile east of An Cheathrú Rua (Carraroe) and opposite the fishing/ferry port of Ros an Mhíl. For their efforts they received three pounds and ten shillings and after having some tea, bread and butter, decided to head back for home. Allowing for almost a hundred years of inflation, this would represent about €275 today.

|

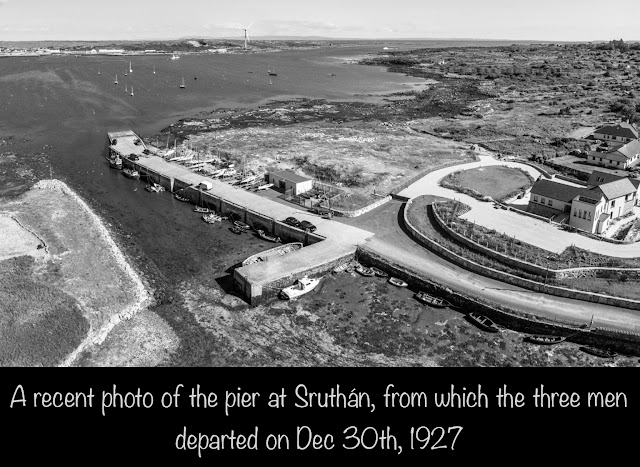

| Showing the port of Ros an Mhíl in the distance. (Photo Michael Harpur.) |

As far as we can tell the breeze was blowing from the Northeast and it was a long journey to attempt on a wintry afternoon. However, the hugely reduced weight after offloading the fish may have given them confidence. The threat of being marooned on the mainland may also have been a factor.

|

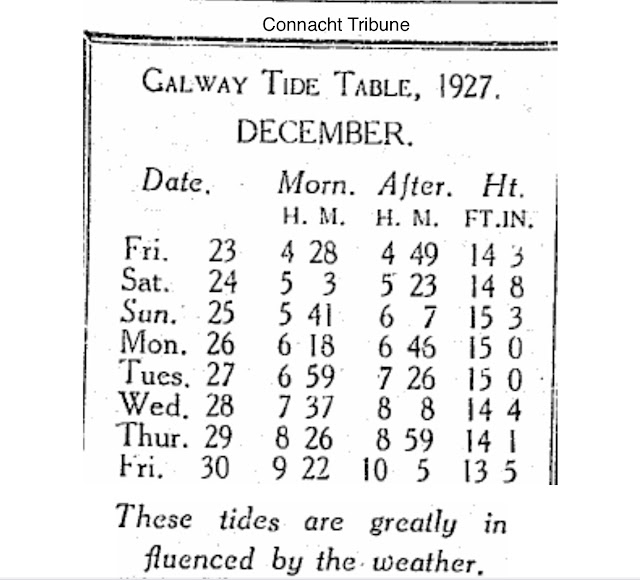

| Tide Table for December 1927 |

It seems the Connemara people had advised them to wait until the next day but one of the men was anxious to set off. Despite the fading light they would have been confident that the powerful Lighthouse on Óileán an Tuí would guide them safely home.

At about 5pm, as darkness fell, the little boat was struck by a powerful and bitterly cold squall. At this stage they were about two or three miles from home and later it was reported that they had even been spotted by an island woman before the wind, sleet, fog and darkness descended.

|

A currach can withstand incredible weather just as long as it can avoid rocks and as long as the oarsmen can keep the head up in the wind. The fact that they had left in a hurry without food or water was now a serious problem.

The three men battled fiercely to keep their little boat from being swamped, in wet and bitterly cold conditions. Myles would later recall that the squall did not last long but the lull that came after was accompanied by a thick bank of fog.

While storms and rough seas were always unwelcome, nothing compared to the crippling effect of fog in the days before radar and satellite navigation.

After rowing for hours, they at one stage spotted Ceann Gainimh (Sand Head) off Inis Meáin but before they could reach shore, the fog descended again.

Exhaustion from both the effort and the conditions led to Michael Burke collapsing to the floor of the currach, some believed, after he had lost an oar. Some time later, Pat Conneely was similarly overcome and Myles Joyce continued to stay at his oars and try to keep the bow up to meet the waves.

It was a bitterly cold time of the year with snow falling all over Ireland and further east, in England and Wales, rivers were reported to have frozen over for the first time in living memory. While the West of Ireland has generally milder temperatures, it has to contend with more frequent winter storms.

According to Myles, he himself became exhausted some time after but luckily the storm had not returned and he remembered falling asleep at the oars. On waking, he touched the forehead of Pat Conneely but found it cold and guessed he had died. Calling out in the darkness to Michael Burke, there was no reply and Myles figured both men were dead.

All day Saturday, New Year's Eve, the little boat drifted in foggy Galway Bay, with two dead men and a semi conscious survivor, lying on its sodden floor. At this stage Myles had almost given up hope of survival and felt he would soon join his two companions ‘Ar Slí na Fírinne’. The last day of the year looked like being his last day on Earth.

|

| Map of Galway Bay. |

At about 1am on New Year’s Day, 1928, the currach finally drifted to land at Loughanbeag near Inverin and Myles Joyce crawled ashore. He was lucky the boat wasn’t smashed on the rocks as these shores had claimed many a fisherman in days gone by. We featured recently a story which mentioned a Claddagh boat belonging to the widow Hernon being lost, along with all aboard, around this area in January 1835.

Myles was unable to stand and was forced to crawl through a pool of water and then crawl again to a nearby house.

Seeking help, Myles knocked on the door of the first house he found but the family inside would not let him in. Those were hard times and the lawlessness that ensued during both the recent War of Independence and Civil War made people fearful of the knock on the door at night. One can appreciate their reluctance to open the door to a confused and bedraggled giant of a man at such a late hour.

Myles was admitted at the next house and in later years he described just how poor the people were but little as they had, they shared with him. They made him as comfortable as they could and summoned help. This was just a few years after the near famine conditions in parts of the West of Ireland, in 1924/25.

The family in the first house arrived and offered as much help as they could. The innate hospitality of Connemara people is well known and they were extremely upset at having misread the situation when Myles had knocked at their own door.

This area had its own share of tragedy just a few years before in June 1917, when nine men were killed after a WW1 mine, which came ashore on the beach, suddenly exploded.

|

| Monument to 1917 disaster. |

Radio transmission was in its infancy in 1927 and the recently arrived lifeboat would operate without one for the next ten years or so. When the men failed to return it was assumed that they had stayed in Connemara as their slow journey there would have been observed locally from the shore or they may have told other boats of their intentions.

The recently established local lifeboat, RNLI William Evans, ran on petrol and had a top speed of just nine knots. On this occasion it was not called out but it would later however be involved in some daring rescues before being replaced in 1939 by the former Rosslare boat the K.C.E.F.

The authorities responded quickly and on January 2nd 1928, inquests were opened at Loughanbeag on the two dead islanders by the coroner, Solicitor John S Conroy of Dangan House in Galway. This was the same coroner who had presided at the inquest in 1924 into the drowning of Myles’ older brother Michael, who was lost off his fishing boat at Galway Docks.

Amazingly, Myles Joyce gave evidence even though it was obvious to all present that he was still in a bad way after the horrendous experience, both physical and mental, he had endured less than two days previously.

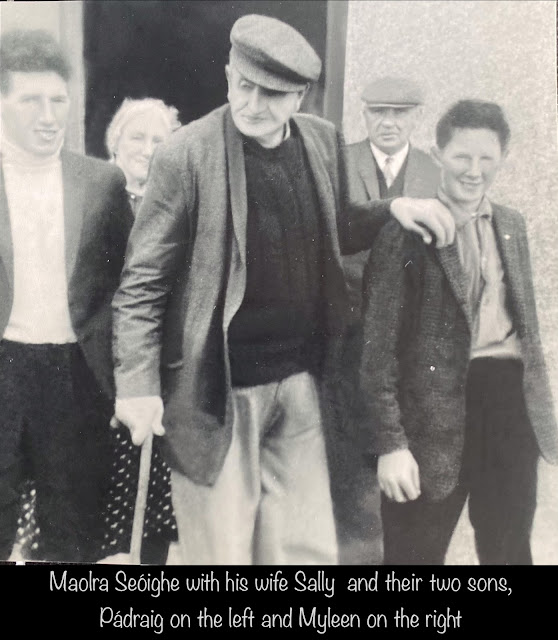

Myles was described as being ‘of splendid physique and standing about six feet three inches tall’. He was known on the islands as Myla Mór (Big Myles) which is no great surprise. His late son Myles was of equally magnificent physique but was known as Myleen Beag, or Little Myles.

|

| Part of a newspaper report in January 1928 |

The survival of Myles was extraordinary and can be put down to his great strength, youth and determination. He had served in the newly formed Irish Free State army in 1922 and it’s likely that his military training contributed to his ability to endure.

|

| Myles on left in his army uniform with Martin Conneely |

The medical evidence from Dr. Joseph Sexton of Spiddal was that the two men died from exposure. The court recommended that the fund established to assist the many families of the dozens drowned the previous October and known as the Cleggan disaster, be contacted with a view to extending their remit to cover this tragedy.

|

| A photo of Myles, taken shortly after the ordeal. |

As far as we know, this never materialised and the Burke and Conneely families were never to be assisted by the fund. It’s likely that in the process of looking after the many families in West Connemara and West Mayo, the smaller Aran disaster was overlooked and fell between the cracks.

At the time of the disaster, Myles was planning to emigrate to America and had made preparations by securing a passport in September 1927. Fate determined that he remain and some years later he married Sally Conneely from Inis Meáin with whom he had three children.

In later years, Myles suffered from arthritis and deteriorating eyesight which was greatly contributed to, it’s believed, by the thirty six hours he endured in freezing cold weather, in an open boat. In his last few years he was completely blind but could recognise every voice on the island.

Given his great physique, it’s likely that if Myles had managed to get to America he would have been a valued addition to the New York or Boston police or fire departments. Two of his brothers were policemen and served An Garda Siochána with distinction, while one brother and two sisters emigrated to America.

The same fine Joyce physique will be remember by many in Galway who saw Myles’ nephew, the late John Joyce, when he performed heroics on the rugby field while playing with Corinthians in the 1970s.

Myles returned to fishing not too long afterwards and being located at the eastern end of the island, was regularly called out to take passengers to the smaller islands. The priest and doctor were often aboard and especially the agricultural instructor, better known in Aran and Connemara as ‘fear na bhfataí’ (potatoes man).

|

| Máire Joyce, as a young nurse in America |

Máire spent many years nursing in America and is retired on Árainn now after returning to help set up the greatly needed nursing home on the island.

Pádraig was a very successful fisherman and owner of first the MFV Carraig Éinne and later the MFV Colmcille before retiring and opening Pier House guesthouse with his wife Máire and their son Ronan.

The youngest, Myleen Beag, died very young after a long illness, leaving behind his wife Neasa and their little daughter, Dearbhla.

We can still remember Myleen firing weights great distances at the local sports in a manner that reminded older islanders of the great strength of his late father.

New Year’s Eve is a special day for us all and on every New Year’s Eve until his death in 1967, Myles Joyce remembered back to the New Year's Eve he spent in 1927, almost frozen to death, drifting with two dead comrades in Galway Bay.

Michael F Muldoon September 2022

(We wish to thank Máire and Pádraic for the help given in the composing of this piece about their late father, Myles Seoighe.)

No comments:

Post a Comment